Funding Child Welfare Services in Pennsylvania

One of the most complex & challenging structures to understand & administer.

The PA Council of Children, Youth & Family Services’ Position & Recommendations

Pennsylvania’s child welfare system is state supervised and county administered, which means that each of the 67 counties has a children and youth agency that manages the services that are available in that county. State and local child welfare agencies rely on multiple funding streams to administer programs and services. Within this multitude of funding streams, each comes with their own unique purposes, eligibility requirements and limitations, creating one of the most complex and challenging structures to understand and administer.

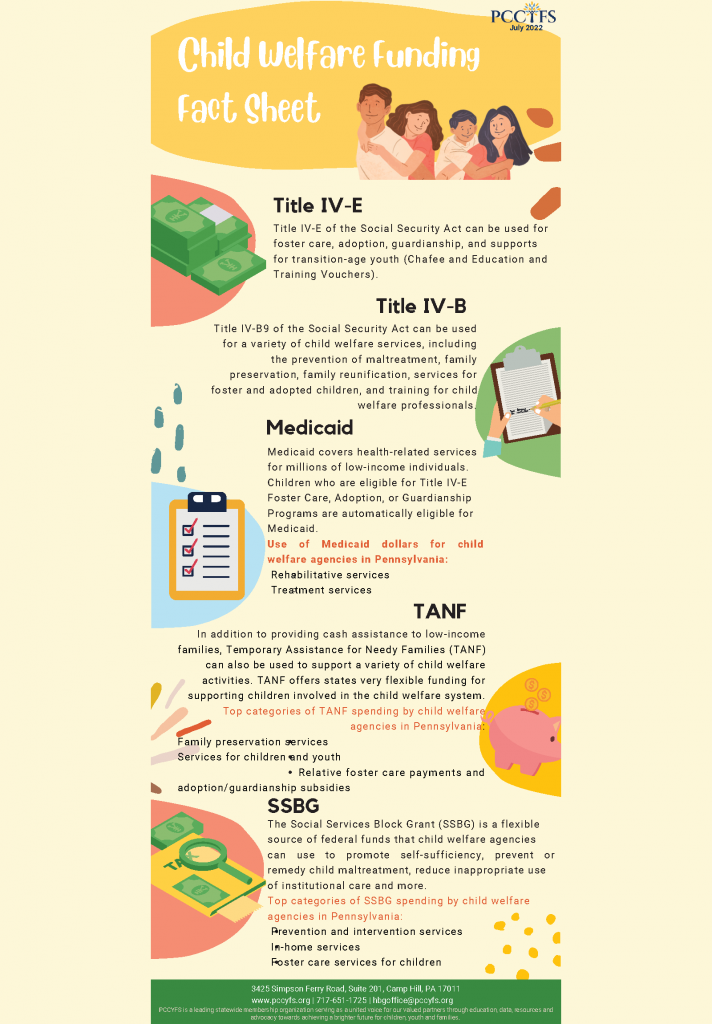

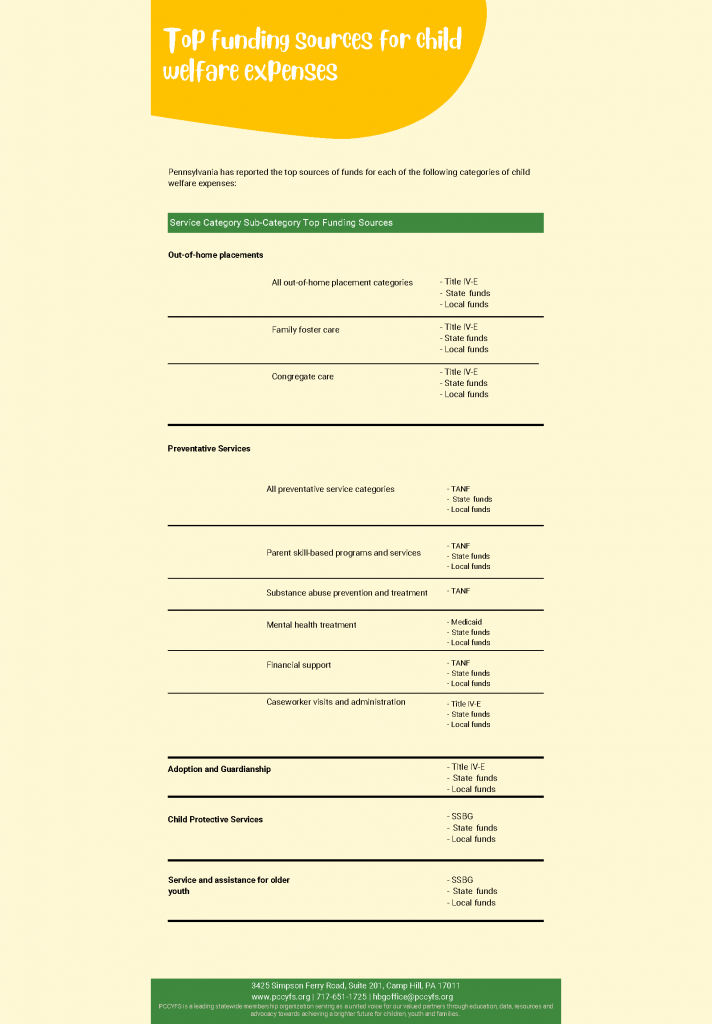

The Pennsylvania Council of Children Youth & Family Services (PCCYFS) has created a fact sheet to summarize the primary funding sources used by child welfare agencies in Pennsylvania and the areas of programming they support. These are not, however, the only funding sources available to Pennsylvania’s child welfare agencies.

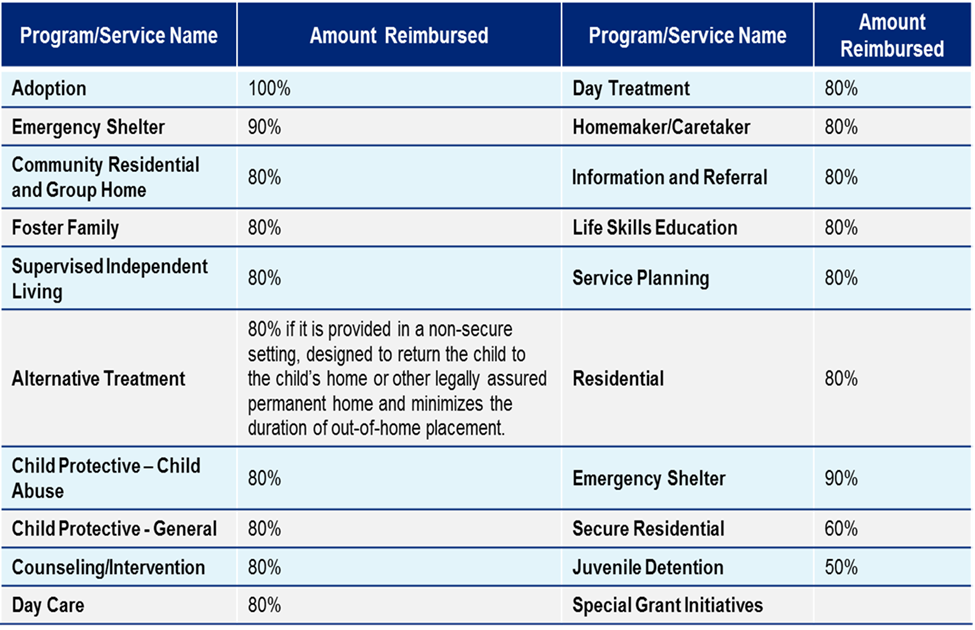

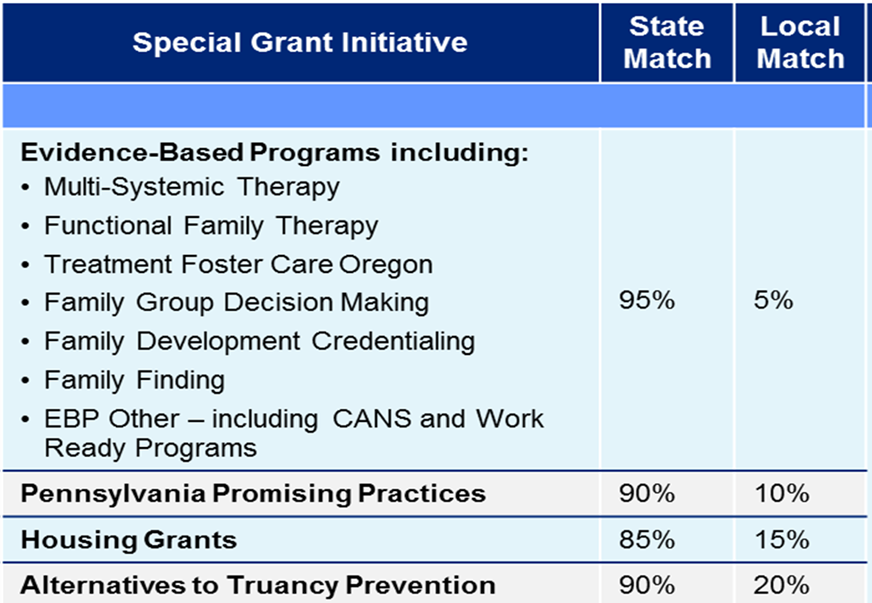

In addition to the complex web of funding sources, there are various reimbursement percentages for services based on state participation rates, which in some cases requires a county match or contribution.

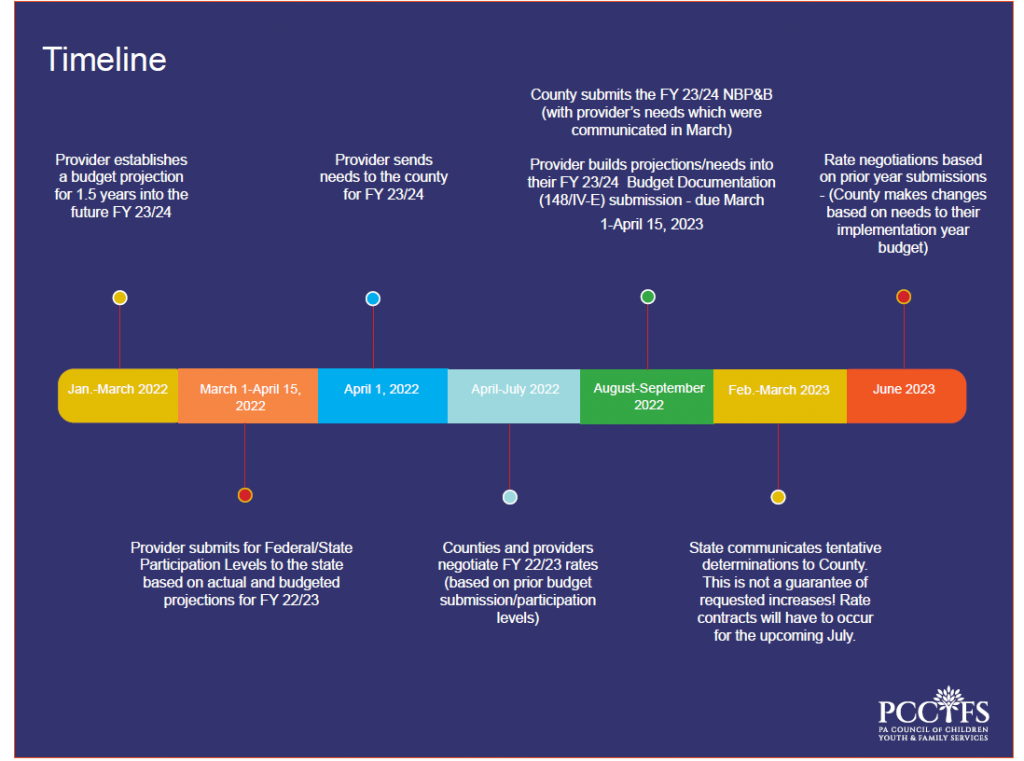

A part of the funding relationship between counties and the state is codified in Act 30 of 1991, which requires an annual Needs Based Plan & Budget (NBPB) process in which counties submit their budgetary needs for services to children and families to the state’s Department of Human Services. County plans must include services for both delinquent and dependent children and should also include costs associated with needing to place children in foster care and/or costs associated with providing children a permanent legally assured family. County plans should include costs for service providers who, in collaboration with county agencies, have designed services to keep children and youth safe in their own homes, prevent abuse/neglect from reoccurring and help overcome problems that result in dependency and delinquency. The NBPB process takes place along a timeline that requires counties to project these costs an entire year in advance. Often, federal and state initiatives, priorities and projects do not line up with the timeline that allows providers adequate opportunities to receive the amount of funding needed to start up and sustain new services or programs. See funding timeline below.

Further complicating the web of child welfare funding, was the passage of the Family First Prevention Services Act of 2018 (FFPSA). FFPSA allows states to receive Title IV-E reimbursement for preventative services provided to families with children at risk of entering foster care and encourages the placement of children with families (kinship or foster). Also, FFPSA creates changes to the types of congregate care or residential style placement settings eligible for federal reimbursement by limiting a state’s ability to submit claims for federal dollars if a child’s stay in a congregate care setting has exceeded a certain period of time. While promising in theory, FFPSA lacks new funding to support this work and does not account for what happens in reality as noted in the diagram below by Sean Hughes, Managing Director of Social Change Partners in “Expectations, Limitations And Reality.”

While we support the state supervised, county-based system in Pennsylvania, the structure creates complexities in funding child welfare services that results in a undesirable impacts to the children and family that the systems are designed to strengthen.

- Currently, through provider cost reports for providers who provide services to children in placement settings, the state sets a maximum allowable rate, which is the amount a provider should be reimbursed for their full cost of care. Counties and providers then negotiate a payment rate, commonly agreeing to a rate that is lower than their true cost of care.

- For in-home service providers, there are no standardized methods for setting rates and therefore some providers are paid rates for services provided to children and families in their own homes at rates that do not account for the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers Urban (CPI-U).

- Pennsylvania limits the use of program funding for programs and services to two years and forces counties to implement fee-for-service structures that often do not cover the true costs of services.

- Similarly, for Medicaid-funded providers that rely on reimbursement through Behavioral Health Managed Care Organizations, negotiated rates rarely reflect the actual cost of services.

Given the state supervised county administered structure of Pennsylvania’s child welfare system, the health of the system is dependent on the financial health of its service provider community. In addition, the availability and array of services for children, youth and families directly correlates to the protection and well-being of children.

PCCYFS POSITION

As Pennsylvania, like many other states, prioritizes protecting children and supporting families through more community-based services, we must ensure the viability and survivability of human services organizations to have sufficient resources to cover their expenses. Private human service organizations cannot devote efforts to innovating, improving, expanding services, attracting and retaining high quality staff, which enhances continuity of care, service quality and administrative efficiency, if they cannot meet the basic requirements of policies, procedures, laws, regulations and bureaucratic redundancies that threaten their stability.

To advance the viability of Pennsylvania’s critical safety net of services, PCCYFS recommends the allocation of state and local funding to fully support the evolving and unmet needs of the children and family services system to ensure an effective continuum of care from Prevention – to Treatment – to Placement – to Permanency.

Such efforts must include:

- In-Home Service Providers the ability to receive increased rates that occur at fixed intervals annually to account for the inflation as per the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U).

- Placement Service Providers the ability to receive the state maximum allowable rate to allow counties and providers a way to create unique service models without assuming unsustainable risks, as done in Colorado through amendments to their Human Services Code, section 26-5-104.

- In behavioral health, it would also mean the ongoing support of models that promote whole-person care while recognizing the importance of increased access, improved service use, and system creativity.

Rate increases go towards staff salaries and make wages competitive – We need rate increases far more than we need one time retention and recruitment money. A healthy provider community is critical to the ongoing support of Pennsylvania’s communities.

Sources:

PA General Assembly –

https://www.legis.state.pa.us/cfdocs/legis/li/uconsCheck.cfm?yr=1991&sessInd=0&act=30 .

Child Welfare Information Gateway –

https://www.childwelfare.gov/topics/systemwide/laws-policies/federal/family-first/ .

Duke University School of Law –https://law.duke.edu/sites/default/files/centers/publiclaw/hughes_ffpsa-_expectations_limitations_and_reality.pdf .

PA Council of Children, Youth & Family Services – PCCYFS Child Welfare Fact Sheet .

PA Council of Children, Youth & Family Services – Needs Based Budget Timeline .